It’s late afternoon on a cool autumn day at the Don & Sallie Davis Boys & Girls Club on Milwaukee’s South Side, and Cedric Gardner is taking charge. Under his direction, a group of young dancers has moved the school desks—usually reserved for journaling and self-reflection—into the center of the dance studio to give it the feeling of a classroom for a seated dance sequence. Think hip-hop meets homeroom.

“Look up when your hands hit the desk,” Gardner instructs the group, shutting off the music to demonstrate how those seated should work their arms and upper bodies—it is not easy to dance when you’re sitting behind a desk.

The dancers mirror his movements, and then the soundtrack cues again, backing the sequence that will be featured in a Pepsi-sponsored video to promote recycling in schools through an organization called We Are Teachers. “This time, let’s see you all smiling, too,” Gardner shouts above the clapping beat.

Hands slap down on the desks, shuffling plastic cups as torsos energetically sway. Every face is beaming. A few seconds in, one of the smaller boys pops up on top of the desks and the seated dancers help guide him through to the front. Amid high fives and hip bumps, others toss up empty plastic water bottles that will eventually get scooped into cardboard recycle bins. The message: Working together we can clean up our classroom and help save the planet.

“I never say no to a performance, because I want the kids to have the experience of performing,” says Gardner, whose Davis Dancers, as the students are known, are likely to participate in two dozen or so gigs over the course of a year. “The more they perform, the more confident they become.”

Confidence is a big part of what Gardner seeks to impart to his budding dancers at Davis, where together they’re part of an unusual effort to see how a youth-serving organization with broad reach into underserved communities can provide high-quality arts to young people. Davis is one of six Boys & Girls Clubs sites across Milwaukee, Green Bay, Wis., and St. Cloud, Minn., that are participating in the first phase of the effort, called the Youth Arts Initiative (YAI).

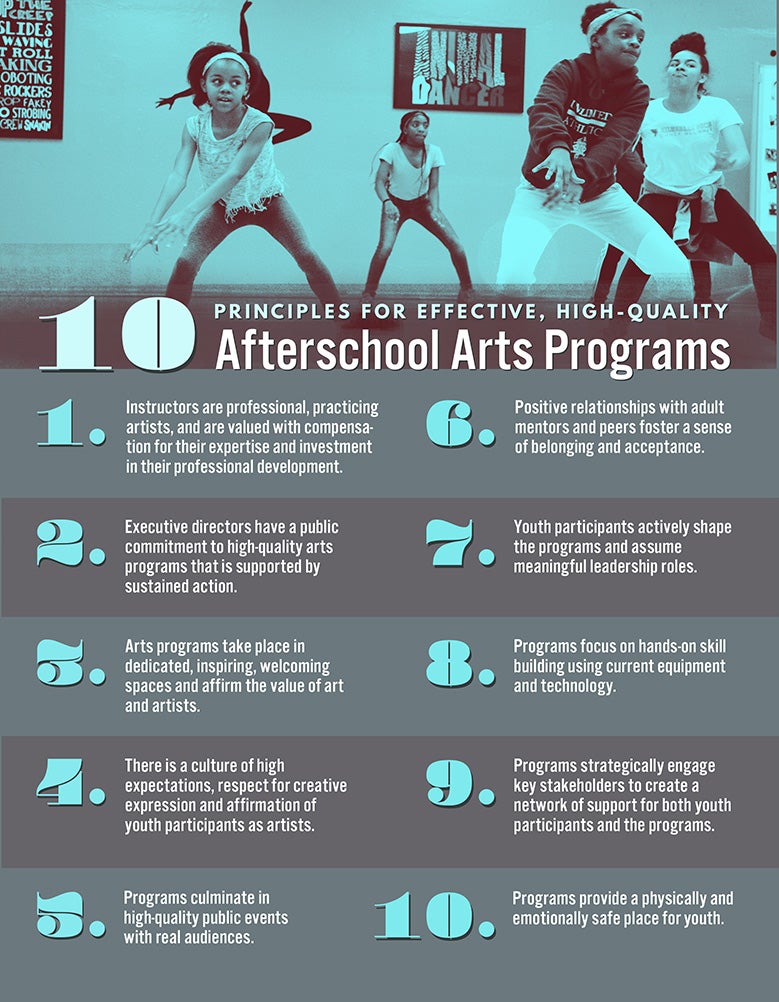

With support from The Wallace Foundation, YAI launched in 2014 to develop a model for offering first-rate instruction in the arts—dance, visual arts, video, music, digital arts and fashion design—to tweens and teens. The initiative calls for sites to adopt, or appropriately adapt, 10 principles of high-quality youth arts programming identified by researchers in a study of exemplary afterschool arts programs—from establishing a culture of high expectations to engaging local stakeholders to equipping dedicated studio spaces with the latest tools and technologies.

Number one on the list of principles is the conviction that instructors should be professional working artists who are willing to carry out the other nine principles while also addressing the day-to-day needs of youth in the club—whether that means teaching a difficult painting technique, mediating a preteen squabble, planning a video shoot or simply being a thoughtful mentor. “Professional practicing artists hold the key to youth engagement in [out-of-school-time] arts programs,” the researchers Denise Montgomery, Peter Rogovin and Nero Persaud write in their study, Something to Say: Success Principles for Afterschool Arts Programs From Urban Youth and Other Experts. “Young people are drawn to the artists’ knowledge of technique, their real-world experiences in the arts and their energy and creativity.”

Because teaching artists are so pivotal to implementing YAI’s efforts, we visited the Boys & Girls Clubs of Greater Milwaukee (BGCGM) last fall to talk to staff members, parents, youth and a couple of artists themselves. They gave insight on the central role that teaching artists play and shared some of the lessons they’re learning about how to run effective arts programming in a large organization.

Enter the Teaching Artists

“Almost 100 percent of our kids are free and reduced lunch,” says Melinda Wyant Jansen, chief academic officer at BGCGM, citing a common indicator of underprivileged schoolchildren or those living in poverty. “And almost 100 percent are people of color. You can read tons of stuff about the kind of problems they face and the kind of gaps they have. All of the things I can provide for my kids as a parent, just by writing checks, these kids mostly don’t have.”

BGCGM works to make up for that opportunity gap, charging its young members just $5 a year to participate in an array of sports, recreation, wellness classes, academics, community service and other services. Programs to familiarize kids with art are offered at all 51 sites with the hope that an arts encounter will kindle an interest in pursuing further classes or will simply make the idea of art less rarified, according to Wyant Jansen. “Most of our programming is at the exposure level, letting the kids dip their toes in the water and get some experience of the arts,” she says.

As Gardner’s dancers illustrate, the kids in YAI have taken a giant step beyond just dipping their toes. And guiding them to that advanced level required committed thinking and planning to find the instructors who could help them make the leap. Staff at all three YAI pilot locations quickly confirmed that teachers needed a number of qualifications beyond merely being good artists, according to Raising the Barre & Stretching the Canvas, a report that examines the early days of the initiative. Would-be instructors who had never developed an interest in arts education and those who could not manage a classroom or lacked cultural competencies struggled to be effective teaching artists, and a few ultimately left YAI. “There are youth-development skills needed when working with kids that some of our artists just didn’t have, so it was a bit of trial and error at first,” says Lisa Manvilla, a senior area director who oversees 10 clubs on the South Side of Milwaukee.

A self-described club kid who has been working at BGCGM on and off for roughly 25 years and with YAI from its earliest days, Manvilla recalls the dance classes she took growing up. The same teacher—“a typical ballet type,” she says—taught every year and always in the same sequences, in contrast to what she has observed in Gardner’s work with the kids. “When you walk into a class with Cedric, the first thing you see is he’s young, he’s got lots of energy and lots of stories about a project he just did or who he’s been working with in his own life,” Manvilla says. Also, she adds, he truly loves the kids. “You can’t fake that. Our kids know when you’re faking it.”

Gardner’s class encapsulates a key tenet of Principle One, according to Something to Say findings: Teaching artists must have not only expertise but also youth-development experience—or a strong desire to work with kids and learn about youth development. In addition to finding artists in this mold, YAI organizers had to figure out how to make the clubs hospitable to serious engagement with the arts. This was the source of some initial friction, according to survey and focus-group data from Raising the Barre. After all, the 10 principles came from small stand-alone afterschool arts programs. How best to incorporate them into multidisciplinary clubs with broad offerings, where the youth had less exposure to and experience with the arts, was unknown.

Staff members throughout the YAI pilot sites reported tensions surfacing almost immediately from other programs and youth mentors. Typically, they were not paid as much as the artists, did not receive the same level of professional development (Principle One) and did not receive the resources the arts classes had, like a dedicated and well-equipped space (Principle Three). To alleviate some of the tension, staff members in Milwaukee sought to integrate the YAI artists into club culture, ensuring they attended meetings with other staff and made an effort to pitch in on larger club projects so they would become part of the team.

YAI staff also learned to bridge the cultural divide through the art itself. “We started putting up the pieces the kids did throughout the building and inviting people to see the shows,” says La'Ketta Caldwell, director of the arts for BGCGM. When other staff and visitors saw the quality of the art and could then hear the kids themselves speaking about it, Caldwell says, a switch clicked and the 10 Principles began to make sense. Raising the Barre findings, too, confirm that tensions began to dissipate when people saw what researchers cited as the “value of professional frontline content experts, ample and updated equipment and supplies, and dedicated youth-friendly space.”

Still, there is no doubt that the infusion of YAI funds allowed for—and in some cases required—more in-depth processes and procedures than the clubs previously had. In contrast to other programming, YAI involved the kids in determining what type of art they would offer at each site (youth input—Principle Seven). At Davis, one group of kids chose mural arts, whereas a group at the other site chose video production, for example. Once the clubs decided what they would teach where, they arranged for kids to help interview potential teaching artists and contribute to curriculum development. The hands-on involvement helped the young participants feel ownership over the program and was so instrumental to the program’s success that club leaders across all three programs said they planned to expand youth-input strategies beyond their arts programming.

Building a Community

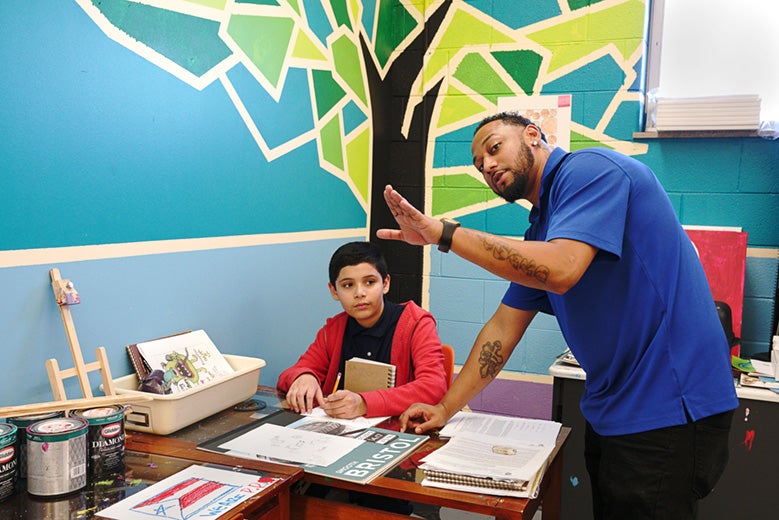

Up on the second floor of Davis, in a small room tucked next to an open space that could double as a cafeteria or gym, Vedale Hill, the Milwaukee native who runs the mural arts program and is now the second full-time YAI staff member at BGCGM, oversees an open studio most days. Filled with kids of all ages and abilities working on projects—some collaborative, some their own—the space has the feel of a Montessori classroom, as Caldwell describes it. The room is covered with drawings in progress, parts of past and current murals. Blotches of spilled paint on the floor have been turned into cartoon characters—"how we deal with mistakes,” Hill says, prompting one young artist to take out his sketchbook and show how he has given these spilled-paint characters even more personality on paper. The entire room buzzes with everything we imagine when we hear the phrase arts education—creativity, collaboration, concentration, patience—a microcosm of the Ten Lessons the Arts Teach, synthesized by the arts-education guru Elliot Eisner in his much-cited work The Arts and the Creation of Mind.

When asked to name the most important skill he’s teaching the kids, Hill doesn’t hedge: creative problem-solving. The kids may be working with the materials and the language of art, but the underlying skills they’re learning, as with Gardner’s dancers, can be applied to their homework, their relationships and other areas in their life. “I’m not trying to make the next van Gogh or Picasso or Kehinde Wiley—or even the next Vedale,” Hill says. “It’s more, how can I teach you to be a better person and think more creatively? To be more involved in your community, culture and neighborhoods? To pick up some skills that can help you navigate life? That’s more important than being able to perfectly render a flower. We got cameras for that.”

Not to say that technique isn’t also important, Hill says, and he has the pedigree to back up his words. A graduate of the Milwaukee High School of the Arts and the Milwaukee School of Art and Design, Hill has become the definition of a community artist. His murals grace walls all over the city. Sometimes he engages the kids to help with commissions from local sports teams, and he always gives them professional credit. With his brother, Hill runs a small arts nonprofit that offers classes to kids from some of the same underserved neighborhoods he lived in. Like many of the kids he mentors, Hill recalls growing up in poverty, moving frequently from place to place. He was heading in a bad direction, he says, when he found art.

Now Hill wants kids from similar upbringings to see art as something that will help fuel their success in life, wherever they take it—or at least to see art as something it’s OK to spend time doing, especially for young African American men. “They can think art is reserved for outsiders or young ladies. It’s not what young men do, so they get made fun of, or they’ll constantly be asked to do stuff for people, like ‘draw this tattoo,’” says Hill. Indeed the Something to Say researchers found engagement in the arts could be so stigmatizing for boys that opting out was the preferred route, despite their interest. “For a tween whose brain increasingly is focused on social standing,” the researchers write, “this combination of arts being outside the norm and having low association with enhanced status creates a significant barrier to engagement.”

In his work with YAI and his own nonprofit, Hill is challenging this and other barriers by insisting that art can be as cool as sports. Part of the coolness factor comes from his own artwork, which incorporates hip-hop and other cultural references, presenting both the beauty and the hardships of life in the hood. Some of it also comes from Hill himself and the rapport he creates with the young people. “He’s been through a really rough time, like a lot of my family,” says 13-year-old Maria Rios, who says she wishes she could be like Hill someday. For his part, Hill stresses the importance of “understanding the cultures, the environment and the context of the young people.”

A Demanding Job That’s Much Appreciated

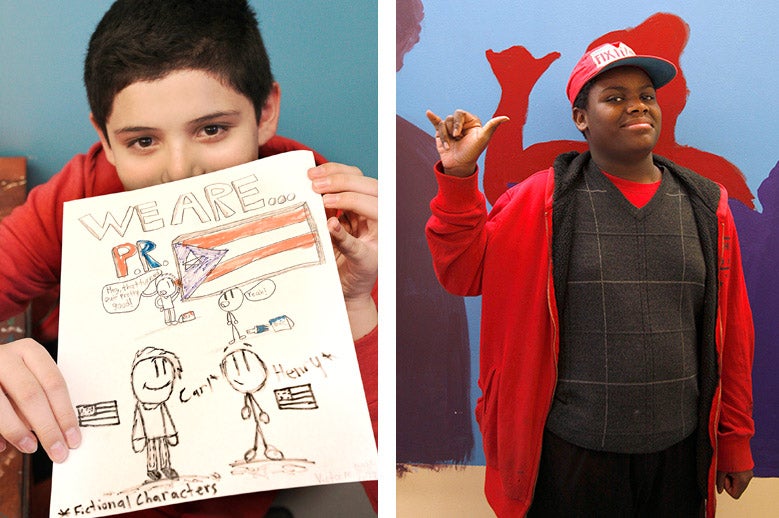

Hill’s deep-rooted understanding of his students is on display in the collaborative projects they have designed together. When we visit, the devastation of Hurricane Maria is still in the news, and Hill’s Davis class, made up largely of Hispanic and Latino students, is working on a project called “We Are PR” that will culminate in a fundraiser for survivors of the hurricane. Meanwhile, a class he teaches at another BGCGM location—Fitzsimonds, with a large group of African American kids—is working on a visual project to address the high rate of vacant properties in the area. Such specificity gives a nod to what scholars and educators such as Geneva Gay and Gloria Ladson-Billings have termed culturally responsive teaching, basically the idea that learning is enhanced when it pertains to kids’ lives and culture.

While Hill’s rapport with the kids may come across as effortless, Caldwell cautions that the depth of the YAI teaching artists’ work takes an enormous amount of time, energy and dedication. “They’re up very late,” she says. Indeed, according to Raising the Barre, 10 out of 12 teaching artists in the three pilot cities reported challenges with their workload; five reported being overwhelmed by their numerous responsibilities. Some of the visual artists described a “one-to-one ratio of prep time needed per hour of programming.” In addition, serving meals and other BGCA duties came with their teaching responsibilities. The full-time teaching artists indicated that they were better able to keep up with both YAI and club duties than the part-timers, but some found they had less time for their own artistic work, undermining a key reason—professionalism—that they were selected for the YAI role in the first place.

The report recommends that BGCA, or any organization seeking to replicate its model, limit the demands on the teaching artist, partially to preserve time for their outside work, which confers an enormous amount of credibility to adults (read: funders), but more important, to the kids. “It’s like, imagine if your high school basketball coach is LeBron [James] and he’s still playing for the Cavs?” says Hill. He’s not being braggadocious, he adds, making the point that enlisting accomplished artists from the start tells the kids that the adults running the program believe in them, that they matter.

Clearly, the kids like what they have seen. In surveys, the YAI participants gave high ratings to the teaching artists on everything from their listening skills to their openness to their high expectations for the class members. And, yes, more than 95 percent of the respondents said their teacher was “very good at the art form.”

Lessons in Art, Lessons in Life

On one of the evenings we visit, Gardner has brought in a friend, also a professional dancer, who’s teaching the older kids to merengue. There’s a lot of laughter accompanying their swaying hips, and they are more experimental than they’ll be for the Pepsi/We Are Teachers video rehearsal the next night. Gardner, whose own credits include a season on So You Think You Can Dance and more recently as an assistant choreographer for the FOX series Empire, agrees that the variety of dance experiences and forms—as well as his professionalism—are all important because they help show the dancers the value of hard work and give them a sense of possibility. He also focuses a lot of his mentorship on modeling how kids should respect one another and their studio space, how to cope with disappointment and, ultimately, how to be a leader. In short, he says, he’s helping them see “how to be a great person…and then be better than great.”

Parents and kids involved in YAI agree that Gardner’s classes bring rewards unrelated to their struts and shuffles. “I strongly believe that dance is beyond the movement of the body,” says Anne Frick, whose 13-year-old daughter Deanna is one of the dancers. “It’s more like life lessons for the children. They learn to help each other out and encourage each other. That’s the main thing, besides the dancing itself.”

Another mother describes the joy of seeing her shy 13-year-old daughter open up “like a butterfly” through the program. Still another says her daughter, who’s 12, has carried her training into her academics. If she’s doing her homework and doesn’t understand something, she and her mother “dance it out” for a bit and then get back to the problem.

On day two of our visit, a mother-daughter duo drops by the studio together, coming straight from the hospital where 13-year-old Heaven has just been released after a bout of appendicitis. “She wanted to see her friends,” her mom, Lisa Novak, says, adding that she also wanted to see Gardner, who has become something of a father figure. Both mother and daughter talk about Heaven’s previous “bad attitude”: acting out in class and at home, talking back to teachers. There’s been a complete turnaround since she started dancing. Her grades have gone up, too. “I used to see the world as somewhere I didn’t want to be,” Heaven says. “I was always at home doing nothing, watching TV. Now I never want to be at home. I’d rather be coming here or doing work or something productive.”

Other kids have seen different rewards. Fifteen-year-old Davian Holton, who was bullied in school, says dance became his “go-to person,” there when nobody else was. One day he wants to open his own dance studio to give other kids the chance he has been given. Or Maria Rios from Hill’s class, who says she used to mess up a lot until she discovered art could keep her mind “out of trouble and bad stuff.” She’s since created a multipiece visual arts project called Keep Calm and Love Art.

Despite these successes, the question is whether BGCA will be able to expand the lessons learned through YAI to more of its 4,300 clubs around the county. The second phase of the effort is expected to roll out versions of programming that seek to maintain its quality but at a more affordable cost. Staff in Milwaukee, meanwhile, are thinking about their own future strategies—short of cloning Hill, Gardner and the other teaching artists—now that Wallace funding for the three YAI pilot sites is coming to a close. The organization is testing expanded partnerships with local arts organizations, for instance, and experimenting with ways that older teens can help mentor younger ones to lift some of the burden off the teaching artists, which seems like a natural progression if you watch and listen to kids who’ve been in the program for a few years. “The thing I’m learning through this entire dance club is that you really need to be, like, a leader,” says 13-year-old Deanna Frick. “As you grow as a dancer, you have to pass through so many obstacles, even if it’s hard, but you just keep pushing through. And dancing, there are always people on the side cheering you on.”

Gardner’s idea of becoming that better-than-great person floats through her words. He’s teaching them well.

Photography by Claire Holt