Breadcrumb

- Wallace

- Reports

- Cultivating Demand For The Arts ...

Cultivating Demand for the Arts

Arts Learning, Arts Engagement, and State Arts Policy

Summary

How we did this

Researchers consulted four types of research literature and studied how state arts agencies allocated their resources. The team also interviewed arts educators, staff of state departments of education, and other experts to learn what federal and state governments were doing to create demand for the arts.

Support for artists and arts nonprofits has ballooned since the 1960s. But demand for their work has not kept up. This report suggests that states must invest in arts education to stimulate demand for the arts and balance the arts economy.

The report argues that state arts agencies could help increase participation in the arts. It suggests agencies should invest in arts education to:

- Help people appreciate the value of art

- Help people create art

- Teach people the history of art

- Create opportunities for reflection on and discussion of art

Such investments could help people find fulfillment in artistic experiences and inspire them to return for more. They also could be especially effective among the young. Studies show that early arts education stimulates arts participation later in life.

Few public schools, however, provide the education necessary to increase demand for the arts. Many schools offer opportunities to create art, but they pay little attention to art history or appreciation. Standards exist for a complete arts education, but districts seldom enforce these standards. And schools receive little help from their state arts agencies. Just 10 percent of these agencies' grants supported efforts to improve arts education.

Steps for State Agencies, Funders, and Policy Makers

The authors present a variety of ways in which state arts agencies should increase support for arts education, including:

- Take stock of existing arts education efforts in their states

- Identify gaps in arts education and support organizations working to fill them

- Help arts organizations replicate successful arts education programs

- Work with national and local organizations to advocate for arts education

Funders and policymakers could support this work by:

- Supporting research into the connections between arts education and arts consumption

- Supporting public-private collaborations to strengthen arts education

- Advocating for changes in state policies to bring arts education to all students

Key Takeaways

- A vibrant arts ecosystem requires more than an increase in the supply of art. It also requires comprehensive arts education to increase the demand for art.

- Comprehensive arts education, especially among the young, can stimulate demand for the arts. But public schools rarely offer such an education.

- State arts agencies can help strengthen arts education. They can invest in research to better understand the improvements needed in arts education. They can help organizations emulate successful arts education programs. They can advocate for greater investment in arts education.

Visualizations

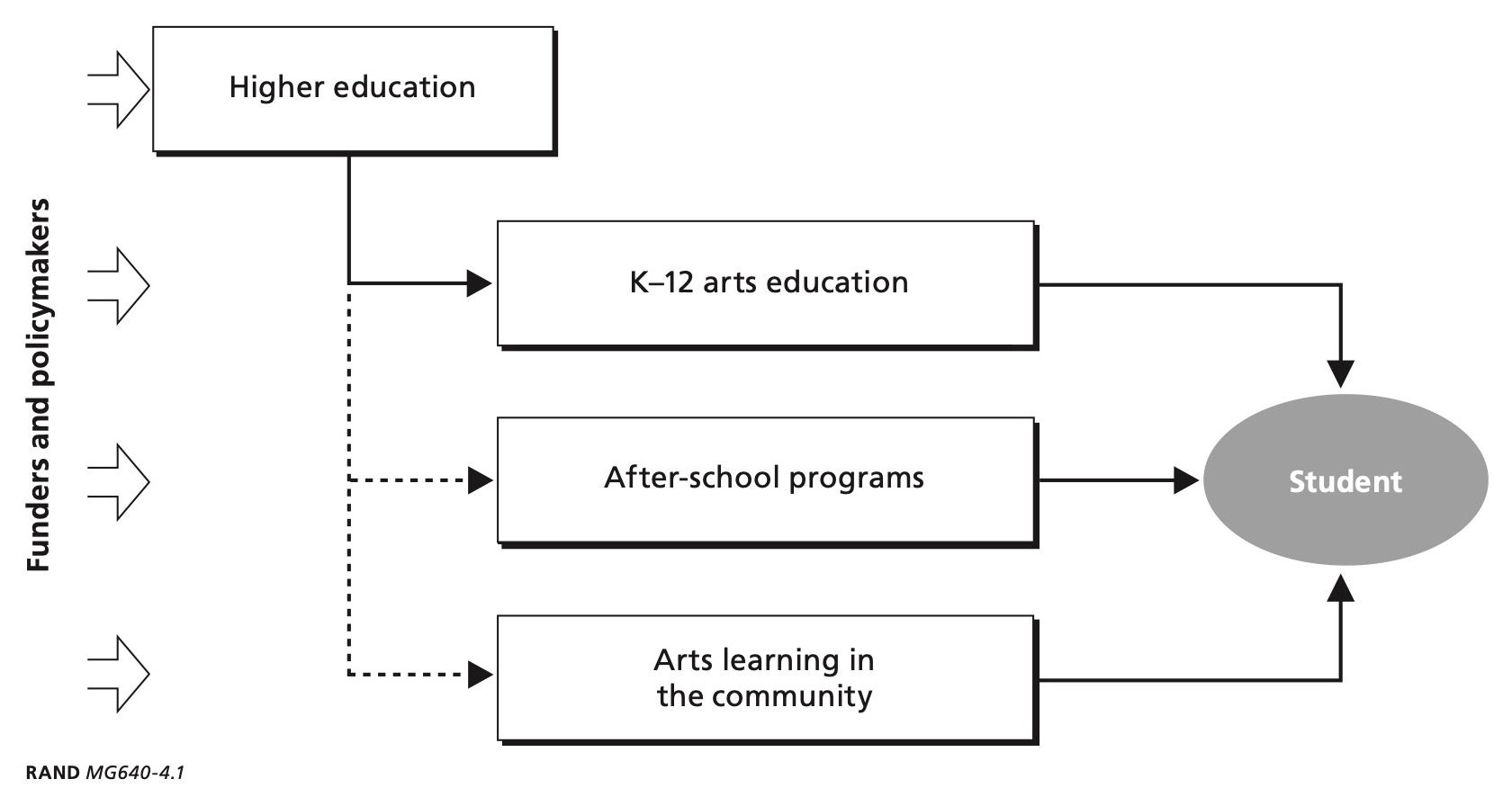

Support Infrastructure for Youth Arts Learning

Materials & Downloads

What We Don't Know

- How prevalent are arts education efforts? Are they reaching enough people to help stimulate demand for the arts?

- What is the relationship between comprehensive arts education and long-term engagement in the arts?

- How can state arts agencies most effectively advocate for increased investment in arts education?

- This study only explores what the National Endowment for the Arts calls "benchmark arts:" i.e., ballet, classical music, jazz, musical theater, opera, theater, and the visual arts. Might it come to different conclusions if it included other art forms?