Breadcrumb

- Wallace

- Reports

- How Principals Affect Students A...

How Principals Affect Students and Schools

A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research

- Author(s)

- Jason A. Grissom, Anna J. Egalite , and Constance A. Lindsay

- Publisher(s)

- The Wallace Foundation

Summary

How we did this

The authors synthesize findings from 219 studies published since 2000. These were culled from a systematic search of 4,800 empirical research studies and other literature. The 219 studies met the authors’ requirements for relevance and rigor. The authors also analyzed U.S. Department of Education data about principal characteristics from 1988 to 2016.

“Principals really matter.” That’s the key finding in this report analyzing research since 2000 about school principals.

The report affirms that effective principals have a pronounced, positive effect on the schools they lead. They contribute to important outcomes like student achievement, reduced absenteeism, and teacher retention. The report also describes the practices that drive effectiveness. And it takes a close look at educational equity and the principal’s role in promoting it.

The report analyzes dozens of studies to find principals have many positive effects on schools and students. These include higher student attendance rates and less likelihood of chronic absenteeism. The effects are higher in urban schools and schools with greater concentrations of student poverty. Principals also affect teachers in areas including job satisfaction and turnover. The report also analyzes the quantitative effects of high performing principals on student achievement and finds significant impacts. But the methods used in their analysis have since been challenged, showing much more modest impacts than are reported here.

Gaps in Representation and Experience

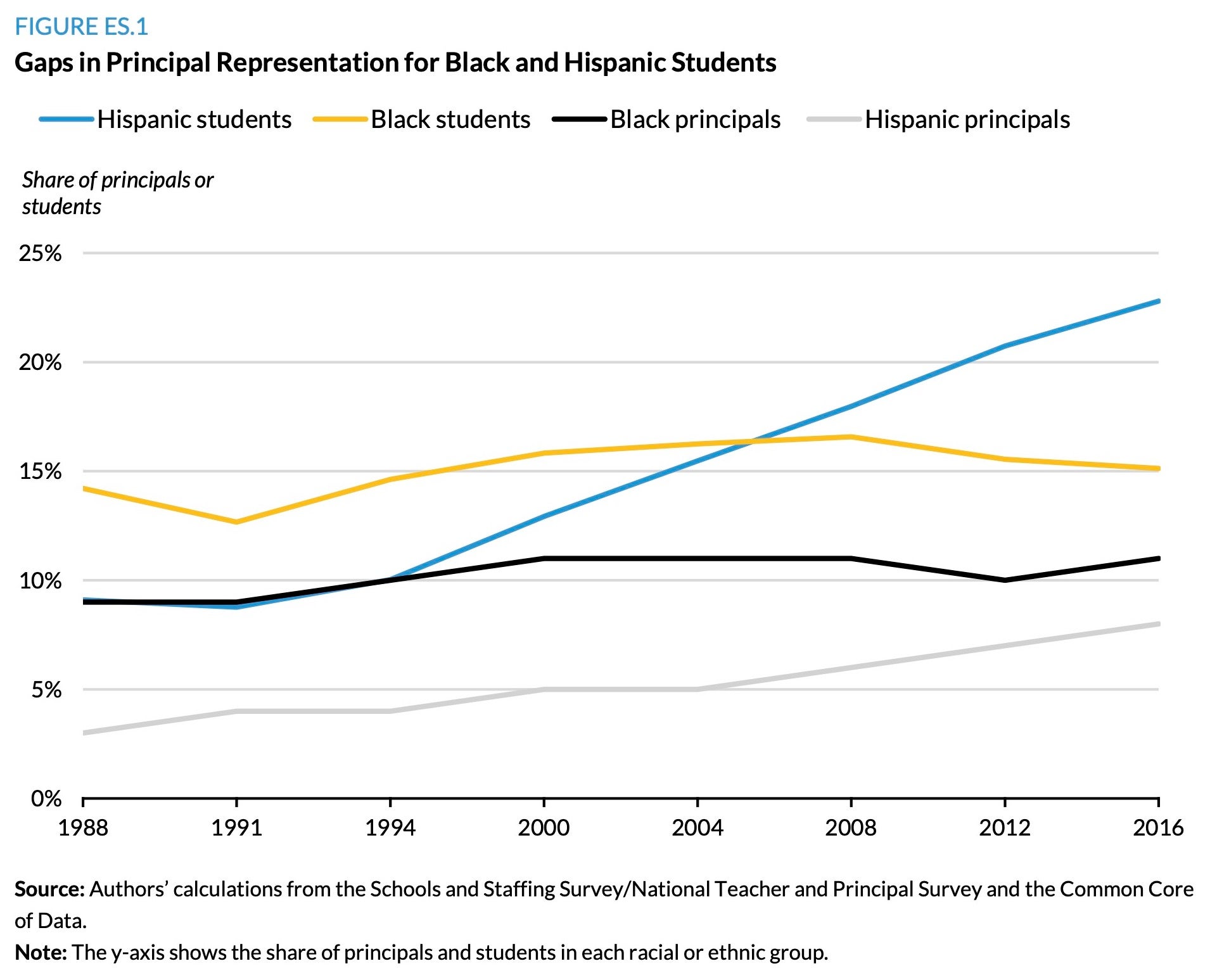

The racial and ethnic make-up of the student K-12 population has changed markedly in recent decades. But the composition of the principal workforce has failed to keep pace during that period, 1988 to 2016.

- For example, in 1988, about 9 percent of students were Hispanic.

- By 2016, that figure was 23 percent.

- Yet the percentage of Hispanic principals grew far more slowly, from 3 percent to 8 percent.

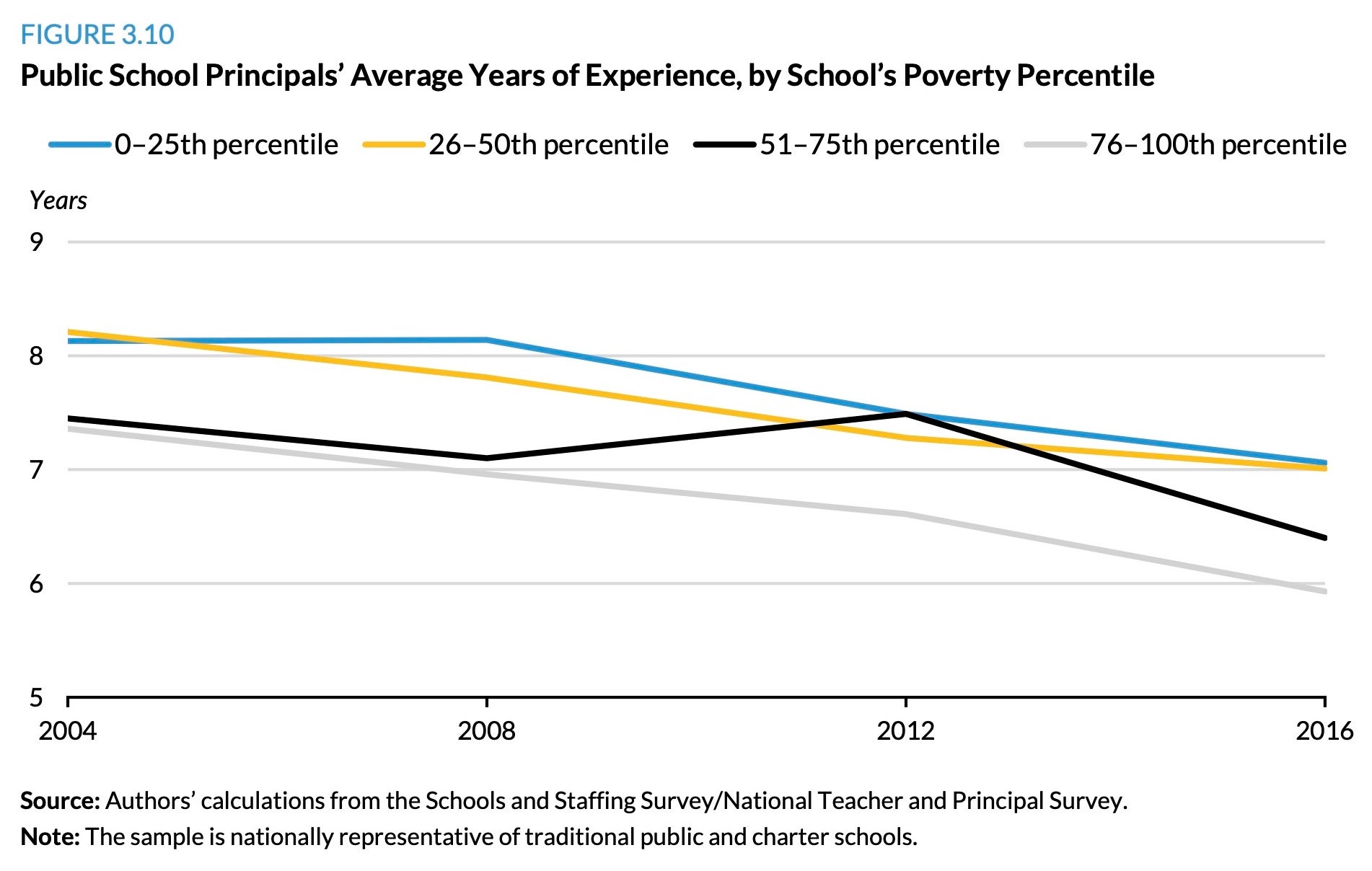

The average amount of experience a principal has had being a principal has declined. That's especially so in the highest-need schools.

- In 1988, principals had an average of about 10 years of experience as a principal.

- By 2016, that figure had dropped to about seven years.

- In the schools with the largest poverty rate, the experience level was less than six years.

In addition, novice principals are more likely to be found in the highest poverty schools. “Declines in principal experience in high-poverty public schools…are an equity concern,” the authors say. That’s because “students from low-income families and other marginalized groups likely benefit the most from having an experienced principal.”

One other point. Effective principals are more likely to retain high-quality teachers and shed the lowest performers. But this pattern, called “strategic retention,” is seen more often in low-poverty than high-poverty schools, where hiring may be more challenging.

Four Behaviors of Effective Principals

Mastery of organizational, people, and instructional skills underpins strong principal performance. They all come into play when principals carry out four key behaviors that the research points to:

- Focusing their work with teachers on instruction. This covers a range of activities, from coaching and evaluation to smart use of data to inform improvements. Some activities often considered important in principal work with teachers may, in fact, not be helpful. These include classroom walkthroughs, depending on how a principal uses them.

- Building a productive school climate

- Forging collaboration and professional learning among teachers and others

- Managing personnel and resources well.

The Behaviors Through an Equity Lens

A growing body of research describes leadership for educational equity and the practices that characterize it. It also leads to questions, such as:

- How can principals remove barriers to equity?

- How can they promote access to resources and supports for the success of all students?

- How can they confront institutional factors that keep certain students from realizing their full potential?

For each of the four behaviors, the authors offer possible answers. For example:

- In instruction, principals might work with teachers to introduce alternative teaching methods that better meet the learning needs of marginalized students.

- In productive climate, they could review and change disciplinary procedures. Would home visits with parents work better than suspensions?

- In collaboration, principals could build stronger connections with families and communities to better serve marginalized students.

- In resources, principals could look at how they assign teachers to classes to make sure that lower-performing students benefit from outstanding instruction.

Declines in principal experience in high-poverty schools are an equity concern.

Key Takeaways

- Effective principals can benefit student achievement and other student and teacher outcomes.

- Racial and ethnic gaps between principals and the student population have widened in recent decades.

- Effective principals are not equitably distributed across schools.

- Effective principals carry out four key practices:

- Focusing on instruction in their interactions with teachers

- Building a productive school climate

- Promoting collaboration and professional learning among teachers and others

- Managing personnel and resources well.

- Principals could carry out these practices with an equity lens to meet the needs of growing numbers of marginalized students.

Materials & Downloads

What We Don't Know

Research on school principals is uneven in its quality and the topics it covers. The authors call for a major investment in a rigorous, cohesive body of research.

Among the questions high-quality research could help answer are:

- Are there barriers or disincentives that drive the principal race/ethnicity imbalance? If so, what are they?

- Why are years of principal experience falling, especially in the highest-need schools?

- What is a principal’s impact on outcomes apart from achievement scores, such as student discipline and improved teaching?

- How can principals make their instructional interactions with teachers most effective?

- How do equity-focused principals carry out the four behaviors?