Breadcrumb

- Wallace

- Reports

- How Leadership Influences Studen...

How Leadership Influences Student Learning

- Author(s)

- Kenneth Leithwood, Karen Seashore Louis, Stephen Anderson, and Kyla Wahlstrom

- Publisher(s)

- Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement

Summary

How we did this

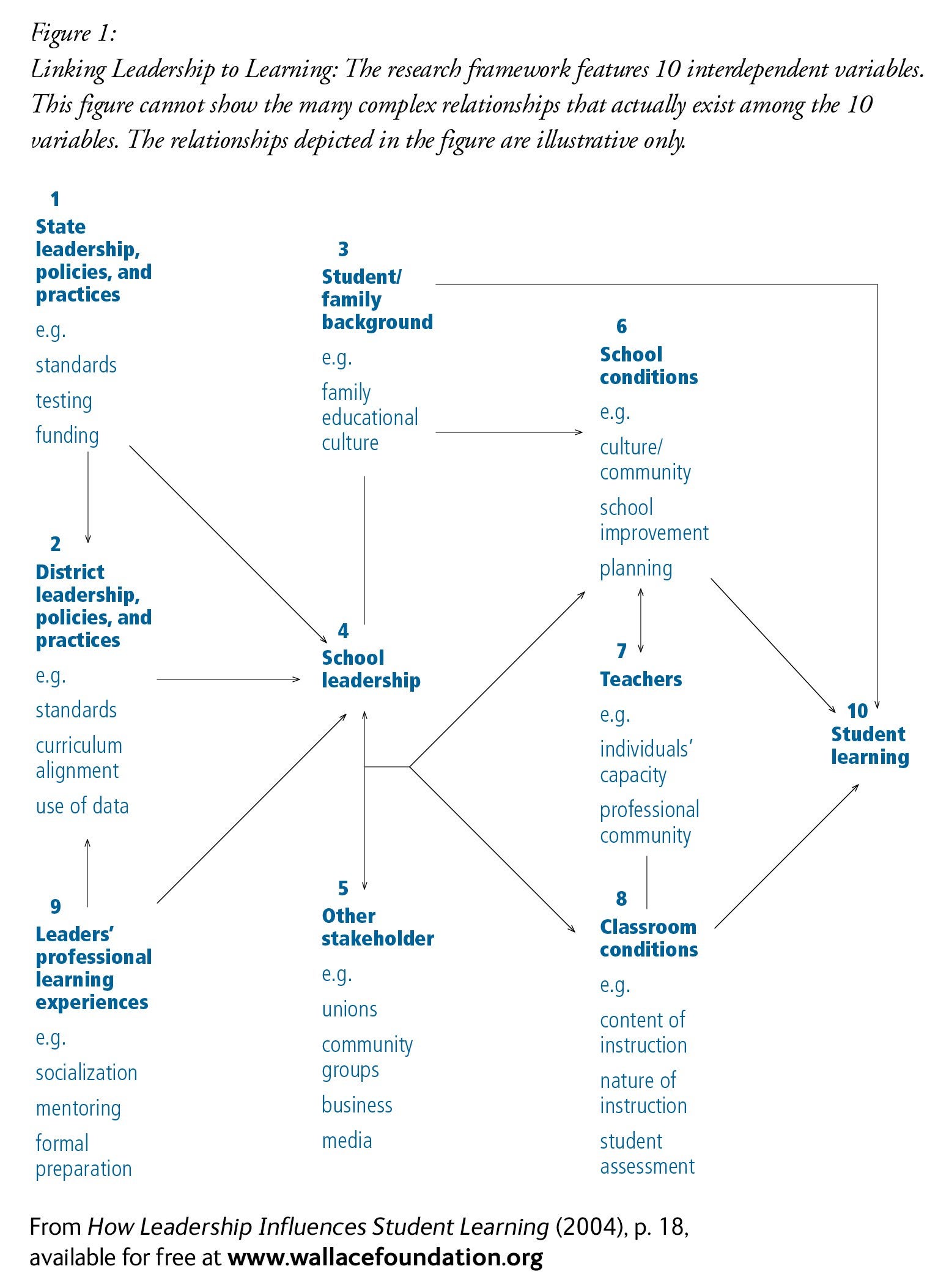

The authors reviewed the existing literature on school and district leadership and its impact on student achievement and practices linked to improved student achievement. They used a framework which emerged from empirical research in sociology and in organizational and industrial psychology.

This landmark 2004 literature review helped establish the importance of principals. It found that school leadership was second only to classroom instruction in school-related impacts on student learning.

A research synthesis published in 2021—How Principals Affect Students and Schools—updated this 2004 review.

Another key finding in the report is that schools in the most difficult circumstances benefit the most from strong school leaders. In fact, there are virtually no documented instances of troubled schools being turned around without intervention by a powerful leader.

The report also found:

- Practices common to school leaders who raise student achievement

- Areas where principals should focus their attention to make the biggest impact on student learning

- Much vague or misleading research on “leadership styles.”

Effective school leaders engage in three “basic” sets of practices:

- Setting directions by helping one’s colleagues develop a shared understanding of school strategies and goals. Practices in this category include creating and monitoring performance expectations. Evidence suggests that the ability to set directions accounts for the largest portion of a leader’s impact.

- Developing people by providing teachers and staff with training and support needed to succeed.

- Redesigning the organization to ensure that conditions support rather than inhibit teaching and learning.

Successful school leaders also go beyond “the basics” and tailor practices to circumstances. “Impressive evidence” shows that good leaders behave differently depending on many factors. These include the size of the school, grade levels served, student demographics, the community context, and state and local policies and resources. That suggests there is no single best model for leadership. The report recommends that principal development programs help school leaders learn a wide repertoire of practices and the ability to use them as needed.

The report describes areas where research shows leaders should focus their attention to have the greatest influence on student achievement. School and district leaders affect student achievement indirectly by influencing people or conditions within their organizations. These include building teachers’ knowledge about how to teach specific content, aligning professional development to school and district goals, and supporting teacher participation in decision making.

The report also describes 12 areas that the literature finds school districts focusing on to improve student learning. Yet the authors find only “correlational” evidence of student achievement rising following district initiatives. Evidence of district initiatives influencing classroom practice is weak.

Discussion of “leadership styles” is often misleading. The report critiques literature supporting particular leadership styles such as “instructional,” “participative,” “democratic,” “transformational,” “moral,” or “strategic.” Often these adjectives mask the similar basic practices effective leaders employ.

School leadership is second only to classroom instruction in school-related impacts on student learning.

Key Takeways

- School leadership is second only to classroom instruction in school-related impacts on student learning. The effect of leadership accounts for about a quarter of total school effects on student achievement.

- The effects of strong school leadership are greatest in schools in the most difficult circumstances. The greater the challenge, the greater the impact of the leader’s actions on learning.

- The common “basic” practices of effective school principals are in establishing a vision and direction, supporting the professional growth of teachers and staff, and creating conditions in the school that support teaching and learning.

- Strong evidence also shows that effective principals tailor practices to specific circumstances, suggesting that there is no single best model for leadership.

Materials & Downloads

What We Don't Know

- How can those in various leadership roles adapt their leadership style to specific circumstances?

- Can more well-developed models of instructional leadership displace the “sloganistic” uses of the term “instructional leadership”?

- How do the ways that school and district leaders delegate leadership responsibilities to others affect student achievement?

- What leadership practices are successful in improving conditions in the school and classroom? For example, how can a leader generate high expectations or foster a faster pace of instruction?

- Research points to school factors important to student achievement that leaders should focus on, such as teachers’ ability to teach specific content. What specific strategies can principals or district leaders to use to strengthen those school factors?