Breadcrumb

- Wallace

- Reports

- Learning-Focused Leadership And ...

Learning-Focused Leadership and Leadership Support

Meaning and Practice in Urban Systems

- Author(s)

- Michael S. Knapp, Michael A. Copland, Meredith I. Honig, Margaret L. Plecki, and Bradley S. Portin

- Publisher(s)

- Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy at the University of Washington

Summary

How we did this

The Study of Leadership for Learning Improvement had three primary strands of investigation: resource investment, school leadership, and central office transformation. The methodology for all three was largely qualitative.

This publication synthesizes three reports that show what is possible when urban districts take improving student learning seriously. The reports analyze:

- How districts that want to achieve equitable learning gains for student allocate staff and other resources

- How school administrators and teacher leaders guide improvements in instruction

- The daily work of central office administrators who develop principals' instructional leadership skills

In this summary report, researchers draw conclusions from the three reports. They explain how school and district leaders can best improve teaching and how they need to be supported.

Leadership Practices to Improve Learning

Schools and districts focused on improving learning pursued some common strategies:

- They concentrated publicly and persistently on improving the quality of instruction. School and district leaders clearly communicated expectations for improvement.

- They invested in instructional leadership. Schools invested in positions such as instructional coaches or teacher leaders. Districts paid for coaching or professional development for principals or teacher leaders.

- They reinvented leadership practices. Central office staff and school instructional leadership teams needed to learn new skills and ways of working together.

- They supported schools and teachers based on individual needs. School leaders and teachers received more individual, ongoing feedback on how to improve instruction.

- They used evidence to focus conversations about improving teaching and learning. Evidence included student work, classroom assessments, and standardized tests.

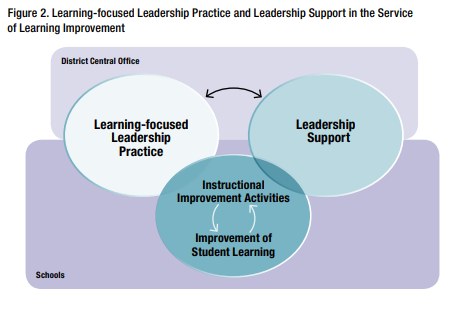

Support for Instructional Practices

School and district leaders supported instructional leadership in the following ways:

- Providing resources to enable leaders to sustain their instructional improvement work. This included structured meeting time for teacher leaders and for district leaders who coached principals. Resources could also include funding for expert consultants or professional development.

- Organizing regular professional development. School leaders and district staff who worked with schools engaged in ongoing professional development to improve their work.

- Providing opportunities for peer networking. Several districts regularly convened the instructional leaders at 20 to 25 schools. Principals, assistant principals, coaches, and others each met with their counterparts at other schools to discuss their work.

- Addressing school administrative or management issues. Districts made central office supports more organized and responsive. This reduced the managerial burden on principals and increased time for instructional leadership.

- Building buy-in for instructional leadership. School and district leaders effectively communicated the rationale for changes to teachers and the community.

Challenges and How to Make Progress

Researchers described many challenges to improving instruction. These include the time, sustained focus, and funding needed to substantially improve. Staff turnover and the many operational distractions urban leaders face are also obstacles.

But the researchers argue that most urban systems can overcome these challenges with strong leadership.

One key strategy is investing in those who coach teachers or principals in how to improve instruction. Another is giving these staffers frequent opportunities for professional learning. The work of districts and school leaders needs to be well coordinated. A shared set of beliefs and approaches to improving instruction helps. So does a thorough understanding of each others' roles and how they fit together.

Key Takeways

This publication synthesizes three reports on how urban districts improve student learning.

- One analyzes staff and resource allocation. A second describes how school administrators and teacher leaders guide improvements in instruction. A third focuses on the daily work of central office administrators who develop principals' instructional leadership skills.

- One key strategy for improving student learning is to invest in those who coach teachers or principals in how to improve instruction. Another is giving these staffers frequent opportunities for professional learning.

- Researchers described many challenges to improving instruction. These include the time, sustained focus, and funding needed to substantially improve.

- A shared set of beliefs and approaches to improving instruction helps. So does a thorough understanding of the district and school leader roles and how they fit together. The work of districts and school leaders should be well coordinated.

Visualizations