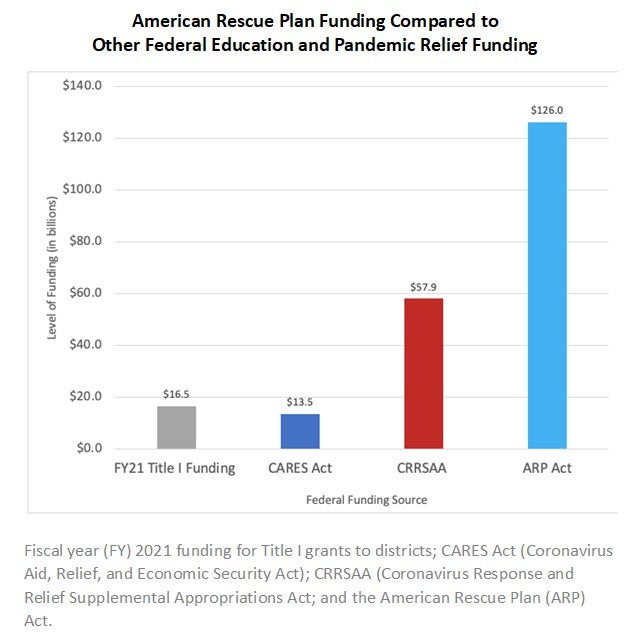

Earlier this year, President Biden signed into law the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act, the federal government’s third major COVID-19 relief bill. The law provides nearly $2 trillion to support the nation’s efforts to reopen and recover from the coronavirus pandemic. Included is more than $126 billion for K-12 schools and additional funding for early childhood and higher education.

These are historic levels of K-12 funding, far surpassing the amounts in previous pandemic relief bills, and they go well beyond annual federal K-12 education investments. Moreover, the relief package could have an impact well into the future, as districts and states are allowed to spend their allotments through September 2024—enabling them to identify and develop solutions that meet immediate needs and seed long-term, evidence-based shifts to better promote equity and improved outcomes.

This description of the ARP, with considerations for states and school districts, was prepared for The Wallace Foundation by EducationCounsel, a mission-based education consulting firm. EducationCounsel advises Wallace and has analyzed the new law.

1. ARP provides at least $126 billion in K-12 funding to states and districts, building upon previous COVID-19 relief packages, to support school reopening, recovery and program redesign.

The ARP includes $123 billion for the Elementary and Secondary Schools Emergency Relief (ESSER) fund—nearly $109.7 billion (about 90 percent) for districts (or local education agencies) and nearly $12.2 billion (about 10 percent) for state education agencies. These funds can be used by states and districts directly or through contracts with providers from outside the public school system.

The ESSER fund also includes $800 million dedicated to identifying and supporting students experiencing homelessness. While not included in the ESSER fund, an additional $3 billion is available under the law for the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Further, the ARP provides $40 billion for colleges and universities (of which $20 billion must be used to support students directly) and more than $40 billion to support the child care and early childhood education systems. For additional information on the other funding provided by the ARP, please see EducationCounsel’s fuller summary of the law.

In addition, the ARP includes hundreds of billions of dollars in State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds that can be used to support early childhood, K-12 and higher education. This includes $195.3 billion to state governments and up to $154.7 billion to local governments and territories. Under the U.S. Treasury Department’s guidance, state and local governments are encouraged, among other possible uses, to tap the State and Local Recovery Funds to create or expand early learning and child care services; address pandemic-related educational disparities by providing additional resources to high-poverty school districts, offering tutoring or afterschool programs, and by providing services that address students’ social, emotional and mental health needs; and support essential workers by providing premium pay to school staff.

2. ARP funding for districts and states is intended to support a wide array of programs that use evidence-based practices to attend to matters including the academic, social, emotional and mental health needs of marginalized students.

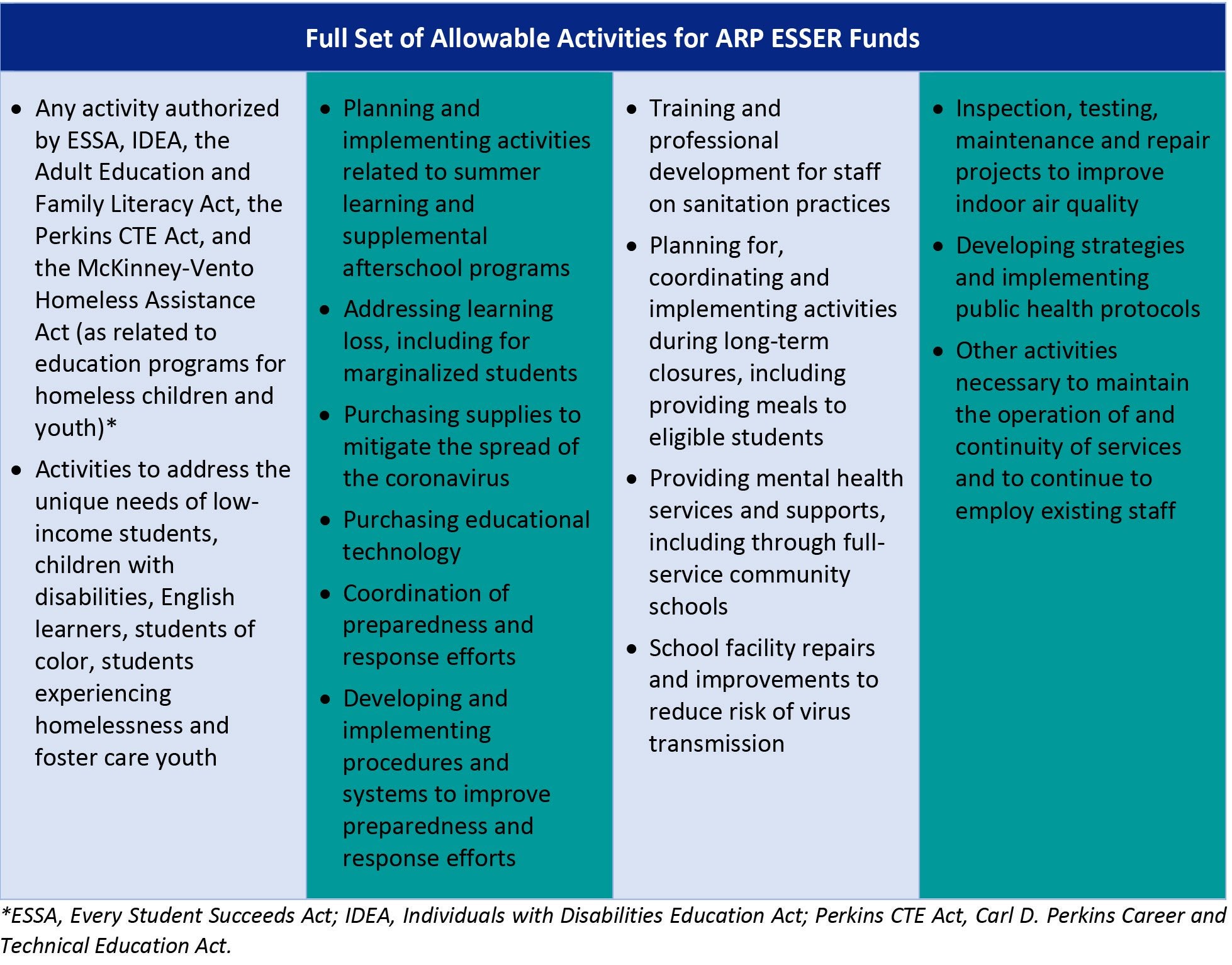

States and districts have substantial flexibility in how they can use their ARP ESSER funds to support recovery efforts and to seed fundamental shifts in their programs and services. Within the text of the ARP and the U.S. Department of Education guidance about the law, states and districts are encouraged to use funds in ways that not only support reopening and recovery efforts but also seek to address the unique needs of our most marginalized students. This emphasis is woven throughout the ARP, including in its state and district set-asides (discussed below) and the provisions focused on ensuring continued and equitable education funding from state and local governments, particularly for highest poverty schools. This equity focus is also inherent in the U.S. Department of Education’s actions to implement the ARP, as evidenced by departmental requirements for state and district ARP plans as well as the department’s guidance regarding use of ARP funds. Equity considerations are meant to help drive state and district decisions to address the disproportionate impact that the pandemic has had on students of color, low-income students, students with disabilities, English learners and students experiencing homelessness. To accomplish this, the Department of Education has described several ways in which the funds can be used. The ARP includes important priority state and local set-asides as well, as described below, all of which must be focused on attending to the academic, social and emotional learning needs of students, and must attend to the unique needs of marginalized youth.

States. Of their $12.2 billion in ARP ESSER funding, states must spend:

- At least 50 percent (or roughly $6.1 billion) on evidence-based interventions to address the lost instructional time caused by the pandemic;

- At least 10 percent (or roughly $1.2 billion) on evidence-based summer learning and enrichment programs; and

- At least 10 percent (or roughly $1.2 billion) on evidence-based afterschool programs.

Districts. Of their $109.7 billion in ARP ESSER funding, districts must devote at least 20 percent (or roughly $21.9 billion) to evidence-based interventions to address both the lost instructional time caused by the pandemic and the crisis’s disproportionate impact on certain students. Similar to the previous COVID-19 relief bills, the ARP allows districts to use funds for activities directly related to the pandemic, such as purchasing equipment and supporting and protecting the health and safety of students and staff, as well as for activities to address the unique needs of marginalized students and any allowable activity under major federal education laws, such as the Every Student Succeeds Act and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

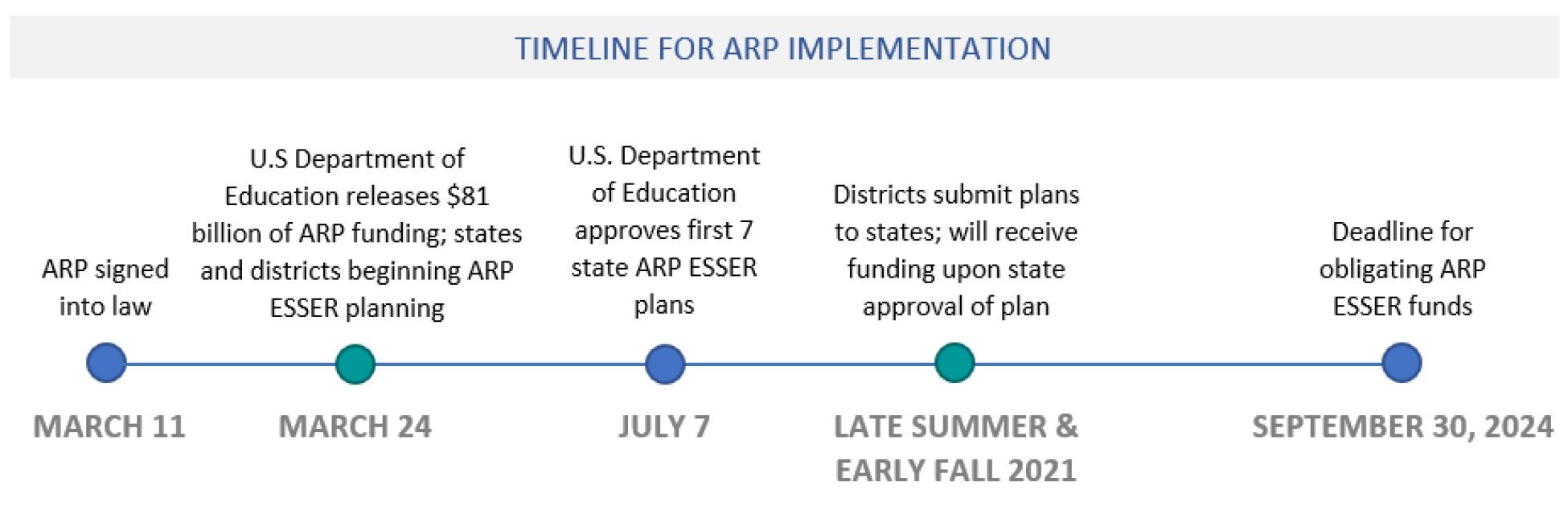

3. Funds are flowing to states and districts and will be available immediately, but they can also be spent through September 2024 to support recovery and redesign.

In late March, states received nearly $81 billion (about two-thirds) of the ARP ESSER fund. Although states and districts were allowed to spend this funding immediately to support efforts to reopen schools for in-person learning or to design and operate summer learning programs, the remaining third of funding is conditioned on states submitting a plan for how they and their districts would use their ARP ESSER funds. Once the U.S. Department of Education approves a state’s plan, the Department will send the remaining funds to the state, and districts will receive their full shares of the funding (via Title I formula) when the state subsequently approves their district plan. The Department has approved plans from several states already and is expected to approve more over the coming weeks. Districts are currently developing their plans, and those should be submitted in the coming months, but timelines vary across states.

While ARP funds are available immediately to support relief and reopening efforts, states and districts can spend funds over several years to promote and support efforts to redesign and improve K-12 education and supports for young people. In particular, districts have until September 30, 2024* to “obligate”—which means to decide on the funding’s use and plan for it through contracts, service-agreements, etc.—their funding. States, in comparison, have a shorter timeline. Within one year of receiving funding from the U.S. Department of Education, states must obligate their funding; however, similar to the timeline for districts, states may spend those funds through September 30, 2024. This three-year period will be critical for states and districts in redesigning how they provide services and supports to students and staff, and states and districts are encouraged to think about this when developing their ARP ESSER plans.

*Per federal spending regulations, states and districts have 120 days after a performance period to fully liquidate funds received. Accordingly, states and districts have until January 28, 2025, to liquidate their funding. Although this provides a slightly longer window to spend funding, we are using the September 30, 2024, obligation as the main deadline for states and districts to keep in mind for planning purposes.

4. The U.S. Department of Education requires states, and districts, to develop plans for how they will use ARP ESSER funding and to revisit plans for periodic review and continuous improvement.

As a condition of receiving their full ARP ESSER funds, every state and district must produce a plan that describes how they will use their share of the ARP ESSER funding, and districts must also produce school reopening plans. Although they are required to submit plans to the U.S. Department of Education only once, states and districts must periodically review and, if necessary, improve those plans. The requirement for states and districts to develop and submit plans is new; it was not a feature of the previous two pandemic relief bills. The requirement also has several noteworthy aspects.

For one thing, to complete the plans states and districts must evaluate and report out the needs of their students and staff, including their most marginalized student groups. For another, states must identify their top priority areas in recovering from the pandemic. In addition, states and districts must consult with key stakeholders such as students, families, educators, community advocates and school leaders.

Below is a list of the seven major areas that the U.S. Department of Education requires each state plan to address, each of which has several requirements:

- The state’s current reopening status, any identified promising practices for supporting students, overall priorities for reopening and recovery and the needs of historically marginalized students

- How the state will support districts in reopening schools for full-time in-person instruction, and how the state will support districts in sustaining the safe operation of schools for full-time in-person instruction

- How the state will engage with stakeholders in developing its ARP ESSER plans and how the state will combine ARP funding with funding from other federal sources to maximize the impact of the spending

- How the state will use its set-aside funding to address lost instructional time, support summer learning and enrichment programs and support afterschool programs

- What the state will require districts to include in their ARP ESSER plans, how the state will ensure that districts engage with stakeholders during the planning process, and how states will monitor and support districts in implementation of their ARP ESSER plans

- How the state will support its educator workforce and identify areas that are currently experiencing shortages

- How the state will build and support its capacity for data collection and reporting so that it can continuously improve the ARP ESSER plans of both the state and its districts

Although they may provide valuable insight into how states and districts will approach using their ARP ESSER funds, the plans may not give the full picture of how the funds will be used—especially for some states and districts. That’s because the plans may not be the only governing documents for states and districts, and the plans can change. In fact, as noted above, the Department encourages—indeed requires in some aspects—states and districts to periodically review and adapt the plans. Plans may also be limited because of current circumstances; that is, it may be difficult for districts and states to be plotting moves several years ahead of time while facing pressing and immediate summer programming and fall-reopening needs.

5. What possibilities and factors might state/district leaders consider when planning for using ARP ESSER funds?

Education leaders and practitioners across the country have faced the pandemic with resilience and compassion for their students and families. They have overcome challenges unheard of only 18 months ago, and they will continue to face an uphill battle as our nation recovers from this pandemic. The funding from the ARP can help in this effort—to address immediate needs and transform our education systems based on evidence and stakeholder input, including what we know from the science of learning and development.

Based on our long history at EducationCounsel of supporting state and district leaders in developing equity-centered approaches and policies, we provide, below, several considerations for sound planning and use of ARP funding. We hope these considerations will offer leaders insights into how they can think longer-term, best support their most marginalized students and those most severely affected by the pandemic, and develop strong systems of continuous improvement.

Don’t just fill holes, plant seeds. The ARP gives leaders the opportunity to provide what their students and families need most immediately, but there is also great need and opportunity to create improved systems over the longer-term. Because funds can be obligated and spent through September 30, 2024, leaders have time to think about the potential of their systems in the next three to five years. While deciding on evidence-based programs that will support current reopening needs, leaders can simultaneously look ahead to how public school education and necessary comprehensive supports for young people can be redesigned and improved. Successful improvements may require additional state or local funding, if efforts are to be sustained long term. Accordingly, leaders may want to consider various strategies to blend ARP funding with other funding sources (including future funding sources) to avoid any funding cliff that may occur when ARP funding ends in 2024. Forming strategic partnerships, building and leaning on the full system of supports for students, and creating community investment will help plant and cultivate those seeds for future progress.

Focus funding on programs and initiatives that will have the most direct impact on marginalized students. The ARP is centered on equity and is designed particularly to attend to the needs of students who have been most severely affected by the pandemic. The U.S. Department of Education has documented the level of trauma such students faced over the course of the pandemic and how this trauma compounds the previous challenges and inequities our students were forced to confront. We encourage leaders to consider how to implement programs that will provide targeted relief and support to marginalized students and those programs that will have the greatest impact on those with the greatest need. This necessitates deep examination of the unique needs of low-income students, students of color, students with disabilities, English learners, LGBTQ+ students and students experiencing homelessness, and how those unique needs may require unique solutions.

Support the academic, social, emotional and mental health needs of students and staff—in schools and across the various systems of student supports. The level of trauma students and staff have faced these last 18 months is unprecedented. Given this, leaders can use ARP funds to create cultures and structures that address the whole spectrum of student needs. This could include designing school and other learning environments, based on evidence, to best serve whole-child recovery and equity by fostering positive relationships, improving the sense of safety and belonging, creating rich and rigorous learning experiences, and integrating supports throughout the entire school. Implementing such efforts and building these cultures was beneficial to students before the pandemic and will be even more important now. School and district leaders might do well to remember the needs of their staff members during this moment, including how developing staff social and emotional learning skills is essential to supporting students’ needs. (We’ve linked to design principles created by the Science of Learning and Development (SoLD) Alliance, on which Scott Palmer serves as a member of the leadership team and EducationCounsel is a governing partner in the initiative.)

Among the questions they might ask are: What needs to be different about welcoming procedures? Do schools need additional support staff? Are teachers and school leaders equipped with the tools and resources they need to fully respond to the circumstances schools now face? How can out-of-school-time providers become full partners with schools, so that students find themselves fully supported in an ecosystem of school and out-of-school-time supports?

Develop current (and future) school leaders to meet the moment. School leaders are central to successful efforts to improve schools and outcomes for students, but no current school leader has experienced a pandemic and interruption in learning at this scale, and principals more than ever need support from their state and district leadership. State and district leaders can use ARP funds to develop and provide guidance on reopening and recovery; provide professional development to support school leaders in meeting the academic, social and emotional health needs of their students; and involve school leaders in critical decision making. State and district leaders can also consider how to balance providing direction to school leaders with ensuring school leaders have the autonomy and flexibility to attend to their communities’ singular needs. Similar to the suggested approach above to consider the needs of the future, state and district leaders can use ARP funding to develop the next generation of school leaders and to support principal pipelines that can both develop talent and diversify the profession. They may also want to evaluate what changes are necessary to existing structures and systems so that future leaders can be prepared to address the long-term impacts of the pandemic.

Regularly revisit plans to analyze impact, identify new needs and continuously improve over time. Recovering from the pandemic and redesigning systems and programs will require ongoing leadership. State and district ARP ESSER plans and strategies should not be viewed as stagnant; instead, they can evolve to meet the needs of students and staff as we progress from reopening to recovery to reinvigorating. By periodically reviewing (and improving) their plans, leaders can help ensure that ARP funds are being used effectively to meet immediate needs, while also evaluating how improvements are aligning to the future. In other words, they can think about the seeds that are planted. To support periodic review efforts, state and district leaders can review data and evidence, consider lessons from implementation and develop feedback mechanisms so that stakeholders are continually engaged and are able to share how funds are (or are not) having the most impact on students’ experiences. It may be helpful for state and district leaders to reevaluate their plans each semester or every six months, at least to make sure that previously identified priorities and interventions are still pertinent to their communities and long-term goals.